Convenience Store Woman (Konbini ningen) by Japanese author Sayaka Murata was originally published in 2016. It’s the story of a rather shy 18-year-old woman, Keiko Furukura, who lands a job at the newly opening Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart, a convenience store in the heart of the business district of Tokyo. 18 years later, Miss Furukura is still working at the same Smile Mart, to the dismay of her sister, Mami, and other family members. They are mystified why Keiko does not want to advance past a part-time job at a convenience store in order to have a real career. Or, at the very least, they think that Keiko should at least be married and try to have a child. They know, but do not understand why, Keiko has never even been on a date.

The Smile Mart is its own clockwork utopia where the needs of customers are anticipated with the help of the day’s weather forecast, special product promotions, the time of year, and other external factors. Similar to the way in which a traveler in Japan’s airports will be greeted by deep bows by the flight crew precisely at the moment of boarding, the Smile Mart follows a set of instructions and guidelines and requires its employees to complete rigorous training. Such details as the type of smile to hold, and the tone of voice to use to cheerfully shout out greetings and sales promotions are included in the training, as well as the specifications regarding the uniform and way to wear one’s hair. The Smile Mart itself is a constantly revolving kaleidoscope of colors, shapes, smells, sounds, lights, and products, all of which create a full and satisfying world for Keiko, who knows her role and how to contribute to maintaining its mechanical perfection.

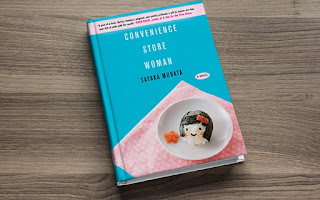

|

| Susan Smith Nash reading Sayaka Murata's Convenience Store Woman. Great beach reading -- fun, with intriguing philosophical and socio-cultural elements. |

The Smile Mart is Pygmalion; Keiko its Galatea in this post-industrial world of constant reification processes, of daily restocking and recreation within the microcosm of the Smile Mart. Because Keiko’s actions are self-directed, however, this automaton has achieved self-awareness. Identity and beingness are self-directed constructs. The constant contact with the ever-changing inventories, light, and dynamics of the Smile Mart constitute the kind of “crossover” (or mixing of genes) that one sees in Japanese mecha (robot) anime. Keiko seems almost to be a the sentient parallel of a mecha / robot.

While Keiko is completely content in her world, she does not enjoy the constant badgering of Mami, her sister, to conform to the social norms for women. So, when the very odd 40-something deadbeat Shiraha is hired on as a part-time worker, Keiko is primed to be receptive in a way she was not before. At first, she finds Shiraha to be utterly repugnant for his slacker attitude and constant ridiculing of employees for being slaves to the system. Shiraha is ultimately fired because his reason for applying for work at the Smile Mart – to catch a wife – resulted in his stalking and harassing female customers.

And, it is at this point that the book takes a very bizarre turn. Keiko stumbles upon the fact that Shiraha is homeless; hopelessly behind in the rent and unwelcome at his family’s home. Instead of turning away, she invites Shiraha to go home and co-occupy her apartment. Shiraha rather unkindly comments that he could never be attracted to her, to which Keiko expresses relief. She considered Shiraha a useful pet; she feeds him, and in turn, he protects her from social criticism.

This made me think of Natsume Soseki’s I Am a Cat (1905), in which the cat speaks in aristocratic tones, making itself superior to humans. I would be curious to know if Murata uses the same sort of high-register, formal diction for Shiraha.

Murata’s ironies are delightful. Instead of being concerned for the actual welfare of the individuals, Keiko’s co-workers and family members are delighted that she is, at least, following social norms, even if her husband is a deadbeat and she is forced to work doubly hard to support him. Shiraha cheerfully and openly explains his goal is to be a parasite, and as such, he will do Keiko a favor by causing her to elicit pity and compassion.

Convenience Store Woman becomes at this point a rather powerful commentary on the role of women in society, and the ultimate lack of self-determination. Shiraha begins to guide Keiko in his own self-serving (and societally condoned) direction, grooming her to take a full-time “regular” job so that she can better support him. But, post-industrial society and its perfectly regulated Smile Marts (and other microcosms) are ultimately safer and happier places. When Keiko finds herself in an understaffed Smile Mart, she steps in, in an instant reanimated and energized. Her identity is restored. She is happy.

Some critics have pointed out the rather Gothic elements of Convenience Store Woman. They are there, but it’s definitely not a full-fledged Gothic novel with dark secrets and bizarre spells and/or a cult of personality. In my opinion, the Gothic elements simply have to do with the rather bizarre hold that Shiraha has over Keiko, and his attempts to harness her to go and work to support him.

The richness of the details that author Sayata Murata provides in the convenience store, not only in the arrangement of products and the sales processes, but also in the dynamics between managers and workers, are such a familiar staple of our world that we immediately identify it as the post-industrial community. In many ways, the Smile Mart and its employees are an extended family, with its members focused on protecting and providing for one’s physical and emotional needs.

On a personal note, I think that Convenience Store Woman should be required reading for all 7-11, OXXO, and QuikTrip employees. I would love to see the transformation, especially if they follow the protocols and customer care concepts found in Murata's novel :).

--- Susan Smith Nash, Ph.D.