Welcome to an interview with Thomas Fink, whose latest collection of poetry, Zeugma, a fascinating title for a rhetorical term that refers to a single word that links disparate ideas ("she broke his glass sculpture and his heart"). It is a great pleasure to have the chance to learn more about his background and some of the ideas that inform his poetics, criticism, and art. In addition to his artistic and scholarly work, Fink has supported publishers and writing programs such as the Marsh Hawk Press.

What is your name and background?

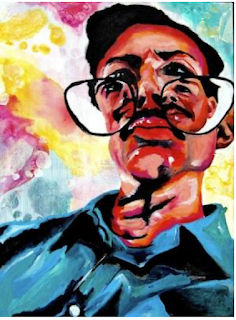

I’m Thomas Fink, a professor of English at City University of New York’s LaGuardia Community College for the past 41 years. I’ve published twelve books of poetry and two books of criticism about contemporary poetry, as well as a recent book on teaching college students to interpret poetry. I “moonlight” as an abstract painter.

When did you become interested in experimental or avant-garde poetry?

When I graduated from Princeton University in 1976 and was just about to enter the MA and PhD program at Columbia University, a high school friend gave me John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror as a present. At first, I found the book infuriating, but eventually, it opened me up to a wide range of avant-garde poetry, and I wrote the third doctoral dissertation (after David Shapiro and Donald Revell) on Ashbery’s work.

What makes a poem experimental or avant-garde... especially in 2023?

I’ve given up trying to answer that question! For one thing, if I were to try to apply it to my own poetry-writing process, writer’s block would set in and persist indefinitely. The innovative practices and procedures that have been around since World War II or even before are still viable but can hardly be called avant-garde any longer. Some proponents of what is labeled Conceptual poetry perceive their poetics as a replacement for those earlier practices, which they consider exhausted and not worth “repeating.” I don’t agree. Others believe that particular kinds of politicizing of poetry, whether tied to formal choices or not, are the most authentic, useful avant-garde gestures. Sometimes I find that this approach produces poetry that is both intellectually and aesthetically compelling.

Please tell us a bit about your collection, Zeugma. What is the main focus?

I didn’t set out to have a single focus in Zeugma. But in her Foreword, Patricia Carlin finds that the title, which implies the yoking together of disparate things, is enacted in the book itself and hence serves as a focus to represent “the fragmented, unstable, and confusing contemporary scene” (9). It would be hard not to view “Bewilderness,” the opening poem, as a reflection on the pandemic, and individual poems surely have references, sometimes oblique and sometimes not, to extremism in the Republican Party.

|

| Zeugma |

I think everyone will recognize the allusion in the title of “November 7, 2020.” A bunch of poems are written in a hybrid form that I came up with called “Sonnina”; it’s a cross between a sonnet and a sestina. Also, there are continuations of long-running series: “Yinglish Strophes,” which uses an approximation (and often an exaggeration) of Yiddish-inflected English syntax to air topics such as intergenerational differences/connections in a family and perspectives forged by immigration, “Goad,” which actually reflects the theme implied in its title, and “Dusk Bowl Intimacies,” which registers both displacements and quests for individual security. The verse-play, “Who My People Are,” may also reflect some concerns of the three series I’ve mentioned.